Art museums used to make me insecure. Between wealthy old people admiring in silence and hip art students wearing avant-garde fashion, I felt uncultured.

Where I saw paintings, they saw gouaches, oils and watercolors. Landscapes to me were triangle compositions to them. What looked novel to me had them smirking at “obvious” references to 18th century masterworks. And while I squinted to read the year it was painted, these cultured people correctly characterized paintings as impressionist, naturalist or baroque.

Most of that was imagined. Many only engage with paintings on a surface level. Even art historians can lack knowledge outside of their area of specialty! Yet I always felt like an imposter, like the works were speaking to me in a language I don’t understand. I felt I didn’t belong—that these halls were reserved for people of real culture.

Today, I feel right in my element. The treasures they contain inspire, console and infuriate. I never leave an art museum without an unexpected idea, a source of inspiration or the seed of a decision.

This essay shares what I learned over the years of going to art museums. All are subjective and based on my own experience. They don’t involve taking long courses or reading textbooks.

1. The meaning of paintings has changed

I used to believe every painting had hidden meaning I hadn’t yet decoded. I faulted myself for not finding the deeper meaning of each brushstroke. Each painting I “didn’t get” felt like a defeat.

Today, we think of art as an exalted pursuit for eccentric geniuses. A late-night walk in Paris produces a flash of inspiration before the artist returns to a paint-splattered studio, where her creativity erupts in her next masterpiece.

We see art as the ultimate self-expression, a tool to share our vision with the world. For modern art, this may be true. Paintings like the Franz Kline below make us want to understand them.

It’s not even always true today, but throughout history, art has served many purposes outside of self-expression. Before the camera, many paintings existed to document, show off and teach.

Look at this Klimt:

While its story is fascinating, Klimt mostly painted rich women from Vienna who paid him well for it. That doesn’t diminish the painting, but it shows not every painting needs a deep reason for painting it.

In realizing that paintings don’t always have meaning, you can free yourself from the guilt of “not getting it” and explore the painting.

Once you’re free from expectation, you can discover what the painting means to you, makes you feel and the questions it makes you wonder about.

This is a paradox: By giving up the need to decrypt a painting, you actually decipher its meaning for you.

2. Permission to dislike

I dislike most of Cy Twombly’s work. Look at this:

I find it meaningless. When you’re at a museum, it’s easy to see paintings like these and get angry at the art world. But you don’t have to like everything.

Fans of action movies don’t feel guilty for not liking romance movies. It’s the same with paintings. You can dislike artists, paintings and even genres.

Feel free to skip what you feel indifferent to. Dive deep into what intrigues you. This is how you cultivate your own taste.

Taste changes. 2 years from now, you might love what you ignore today. If you’re focused on improving your craft, you might admire Velazquez’ masterly portrait:

If you’re in a transitory period, searching for your true purpose, you might feel attracted to De Kooning’s puzzling compositions:

You can dislike or like any artwork you see. Skip what you dislike, linger on what you love.

3. Follow your feelings

I love small museums. There are no famous paintings you think you should like. If no name rings familiar, and your Instagram followers wouldn’t be impressed you saw a certain painting, you spend time with what makes you feel something.

When a painting catches your eye, let it get caught. Like a fish, let yourself get reeled in.

You’ll get a few things out of this: You get to know yourself. What does it reveal about you (to yourself) that this painting attracted you? What does it say about your state of mind?

Look at this Hans Busse painting:

If it catches your eye, you’re probably in a different mind state than if you find yourself mesmerized by this Basquiat:

When you let your feelings guide you through a museum, you’re also more intrinsically motivated to go deeper on a painting.

4. Spend more time!

Harvard art historian Jennifer Roberts’ courses require an in-depth paper on one pice of art. The first part of it is excruciating: Before doing research, you go to a museum and look at it for 3 hours.

No phone, no research. Just you with a notebook, noting observations, questions, insights.

I used to glance at paintings and move on. After all, I’ve “seen that painting”. And if I don’t see everything in the museum, I didn’t get my money’s worth!

That was wrong. I now believe in spending more time with a single painting. I haven’t done the 3 hours with one painting exercise (it’s on my list, just like War and Peace…), but even a few minutes give you more insights.

Look at the Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa, the most impressive painting I’ve seen in person:

At a glance, you see a dramatic shipwreck scene. But if you stay, you might spot that some of the passengers are already dead. Take another look and you might realize the hero figure is black (painted during a time when slavery was alive in France). The second black person to the hero’s left might reveal himself soon after. Stick around long enough to examine the horizon line and the painting rewards you with the tiny ship that’s giving the survivors hope, being both the composition’s smallest element and its entire point.

Many paintings have secrets they only divulge after some time.

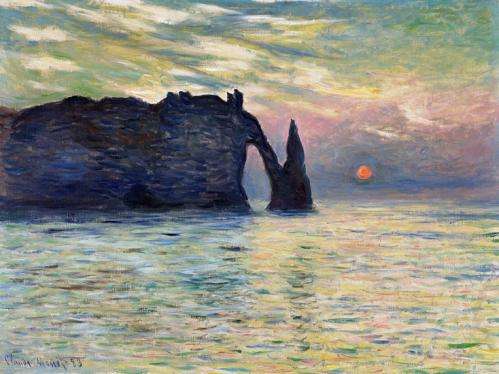

Spending more time with a painting also probes the logical mind: Spend time with the Monet below and you’ll find the consistently horizontal brushstrokes at the source of its serenity.

Go deep on this Degas and you’ll find the dancer’s heads at the same height, creating an impression of order.

You’ll ask yourself these questions and you’ll find answers. And while Jennifer Roberts forbids research, I encourage it.

When I like a painting, I google or YouTube the artist. This gives the experience even more texture. It infuses historical context and gives me deeper understanding based on the artist’s biography.

Standing in front of Picasso’s Guernica, I listened to The Canvas’ video about the painting, which made the experience so much more interesting.

These are the things that made me go from disliking art museums to them being some of my favorite places. While I’ve presented a few things, I want to note that there’s no exam at the end of a museum. If these tips seem like too much at once, pick one the next time you visit a museum.

And that’s where we conclude. I hope you enjoyed reading this essay. But, more importantly, I hope you’ll go to an art museum.

If you want to start on YouTube, I recommend Great Art Explained, The Art Tourist and The Canvas.